The Origins of Stirchley

Stirchley is a district of Telford developed as part of the new town from 1968. Lying two miles south of Telford town centre, the district has a population of some 5000 people.

But almost hidden from sight on the edge of the modern district lies the ancient village of Stirchley, a tiny rural hamlet centred for nearly 900 years on the parish church of St James.

The Old Village

Tucked away in the trees behind the church stands the Old Rectory of St James with a history almost as long as that of its ancient neighbour. Along the lane are a handful of old cottages, one formerly the village butcher's shop, another the old post office. And across the road is the site of the Victorian village school which was taken down and rebuilt brick by brick at the nearby Blists Hill Museum. Just along Stirchley Road is Stirchley Hall, a building dating back to Tudor times.

Agriculture and Industry

Before the 1970s Stirchley was very much part of a farming community, for the most part making a living from rearing livestock. Not all the soil was heavy clay, some was more gravelly and some parts of the parish favoured the growing of cereal crops. Even as late as 1882 the headmistress of the village school noted that when school reopened in September of that year, many of the children had not yet returned because they were gleaning in the fields.

However, Stirchley borders an area that has long been exploited by industry for its natural resources. During the 18th and 19th centuries the area was noted for its coal mines, iron works, china factories and brickworks, industries that can be traced back to the Middle Ages when no less than six local monasteries profited from the coal and ironstone mines and the smithies on their extensive estates.

Canal Transport

Transporting the raw materials and manufactured goods from the area also created changes in the rural landscape. The Shropshire Canal's Coalport branch was cut along the western edge of the parish in 1788.

An industrial tramway from Hollinswood to the River Severn opened in 1799; this entered the parish from the north and passed via the Mad Brook valley to Holmer in the south-east corner of the parish. The tramway closed in 1815.

The Coming of Rail

In 1854 the Madeley branch of the Great Western Railway cut across the south-east corner of the parish near Holmer.

The GWR also laid the Old Park mineral line from Hollinswood to the Randlay valley in 1908 to serve the industries in Stirchley.

And in 1860 the Coalport Branch Railway was built on the line of the canal with a station at the Stirchley-Dawley road. The station closed to passengers in 1952 and the line closed completely in 1964.

By the end of the 19th century the industries were falling into decline and by the mid 20th century the prosperity had gone leaving only the devastation caused by 200 years of exploitation.

Telford New Town - Preserving the Heritage

The creation of the new town of Telford was a quite an achievement. Estates of houses were set in a rural area amongst significant amounts of open green space with preserved trees and hedgerows. The industrial waste left by past industries was landscaped to create parkland while, at the same time, making the most of the industrial heritage. The conserved evidence can still be seen of canals, railways, mines, ironworks and buildings associated with the area's industrial past.

And the planners also had the foresight to preserve little gems such as the old village of Stirchley. And the massive scars left by the industrial past were turned into the extensive green corridor that is now Town Park.

The 1901 Census recorded some 200 people living in the parish, a similar number to the Census of 1841.

About half of the people lived in the village itself, the rest lived scattered around the parish.

And there was roughly an equal split between those who worked on the land and those who worked in the coal mines, iron works and in brick-making.

Stirchley - a Farming Community

Before the impact of coal and iron, a brief report on the parish made in the mid-1700s shows a wholly agricultural scene, though with a size of population probably not much different than that of 1841:

12 houses in the parish, 6 farms and 6 cottages. Situation somewhat high. Land moist and cold. Pasture and meadow. Little arable. Pretty wholsome air.

The growing of crops was not favoured by the heavy clay soil in much of the parish and so the greatest part of the area was used for grazing livestock.

Most of the land remained under grass until the development of Telford new town after 1968.

In 1612 there were only 3 farms and 5 cottages, and in 1563 there were just 7 households.

Anglo-Saxon Origins

The size of the settlement and the use of the land probably differs very little from the Anglo-Saxon farming village almost a thousand years earlier. It is possible that a settlement here may date from as early as the 7th century, but the placename itself is first found recorded in 1004 in the will of the wealthy Anglo-Saxon nobleman, Wulfric Spot, who bequeathed the manor to Burton Abbey.

The name of the village translates from Old English (Anglo-Saxon) as 'a clearing in a forested area where young cattle are kept'.

The Royal Forest of Mount Gilbert

or The Wrekin Forest

The Anglo-Saxon term -ley signified a clearing in woodland. Most of Shropshire would have been extensively wooded in Anglo-Saxon times and significant areas of uncleared woodland survived well into the medieval period. So origianlly Stirchley was a probably not much more than a farmstead set up in a clearing in this heavily wooded country. The clearing may have been a natural one or a one previously cleared by earlier people. Or it may have been settlement set up on land cleared by the founder of the farm.

The woodland around the Wrekin was a designated (royal) forest before the Norman Conquest, covering an area of some four square miles. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, William the Conqueror had created 21 new royal forests, a figure rising to 80 by the end of Henry II's reign in 1154. Both Henry II and Richard I made huge additions to the area under Royal Forest law around the Wrekin. It was then known as the Royal Forest of Mount Gilbert and covered an area of some 120 square miles, a swathe stretching from north of Shrewsbury to east of modern Telford. The forest area eventually became so large that it had to be separated into three ‘regards’, known as the Bailiwicks of Haughmond, Wombridge and Mount Gilbert itself. Stirchley lay near the eastern edge of Wombridge.

In 1232 the lord of the manor, Osbert of Stirchley gave the manor to Buildwas Abbey which continued to hold it until its dissolution under Henry VIII in 1536. In 1277 the monks of Buildwas were licensed to assart 60 acres in Stirchley, when they were establishing Stirchley Grange. Their need for building timber and for agricultural land led to a further major reduction of the wooded area of Stirchley.

The royal forests were set up for the hunting pleasure of the king and strict rules and punishments were put in place to deal with anything that might interfere with the wild game. Courts existed to enforce the law presided over by royal officials known as Verderers. The Forester family were the hereditary wardens of Mount Gilbert and it was their duty to ‘walk the forest early and late’, to watch the venison (deer and wild boar) and vert (the forest), and to present trespassers to the local forest court.

However, life went on. People lived and farmed and worked in the forest. Even in the deer enclosure Wellington Hay, which ran from Watling Street to the Ercall, local people could graze their cattle for most of the year in payment of a fee. At Wellington it cost 2 pence to graze a yearling swine and 1 penny for a six-month-old pig.

The Crown’s constant need for money ensured that many illegal practices, such as pourprestures (erecting buildings) and assarting (clearing the forest for farming) were legally licensed. However, many officials abused their powers for their own gain, and by 1217 Forest Law had become so unpopular that a charter was drawn up to remove many of the more recent additions to the royal forests. During the reign of Henry II one third of Shropshire may have been under forest law but after 1217 the amount decreased sharply.

At the forest assizes of 1250 many local settlements, including Wellington, Hadley and Dawley, were exempted from the ‘regard’ of the Wrekin Forest. These exemptions were often preceded by an official survey, known as a ‘perambulation’, where several officials walked the forest to determine its extent. After the ‘Great Perambulation’ of June 1300 the Norman forest practically ceased to exist and only Wellington Hay remained as a royal demesne, surviving until the 15th century.

Stirchley lay within the Royal Forest until 1300 when the forest law ceased to exist. By this time the woodland of Stirchley lay in the north-east along the boundary with Shifnal. In the mid-13th century individuals cleared more woodland to bring new land into cultivation. The names Brands ('land cleared by burning') and Stockings ('a clearing with stumps') near Holmer derive from this period.

Arable and Pastoral Farming

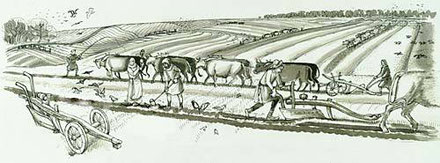

It is not known when the communal open fields of Stirchley were set up. The open field system developed before the Norman Conquest probably during the 10th century. Howevern in wooded areas it would have been much later. Village land was pooled, probably at the instigation of the manorial lord, and redistributed so that everyone had a number of strips in each large field. This ensured that everyone had a share of good and bad land. Such systems traditionally had three great fields divided into furlong strips. These were 220 yards long and 2 yards wide, although the width of strips varied in different places at different times. By c1300 units had been standardised. An acre, originally used to denote the size of a field that could be ploughed by a team of oxen in a day was defined as an area 1 furlong in length by one tenth of a furlong (22 yards) wide. A standard open field was 10 acres in area.

The plough was turned on the outside of each strip to raise the level for drainage and to delineate it from neighbouring strips.

Families rented from the lord of the manor a strip or more in each field, rent being paid in labour or in kind, and later in cash. A traditional crop rotation was peas or beans one year, the next year wheat, barley, rye or oats, the third year the field was fallow ie. left to rest with grazing animals manuring the land.

The open arable fields at Stirchley do not seem to have been extensive by the 16th and 17th centuries and it may be that they never were. Most of the open field system lay in the west of the parish in a field known in the 17th century as the Common Field. This is the area around where the canal was to be cut. There were also small areas of open cultivation in Cross Furlong, immediately south of the village, and in the Lower Field, east of Mad Brook. Enclosure occurred by exchanges of strips between the owners of Stirchley Hall and Grange Farm in 1611, 1695, and 1716, but unfenced strips of glebe (ie. land belonging to the rector) still survived into the 19th century.

Most land in the parish was held as enclosed permanent grassland from the 16th century or earlier, until the 19th century. The pastures in the south belonging to Stirchley Hall had been enclosed by c1540, and most of the rector’s glebe consisted of leasowes in the 17th century. Field names on the 1838 map of the parish are predominantly meadows and leasowes, ie. pastureland. Most of the field pattern that survived into the 20th century had probably been established by the end of the Middle Ages.